As commentators have become more sanguine about future economic prospects, I’ve switched my view relative to the punditry and believe the probability of a recession is higher than is implied by markets. My views may change as more data becomes available.

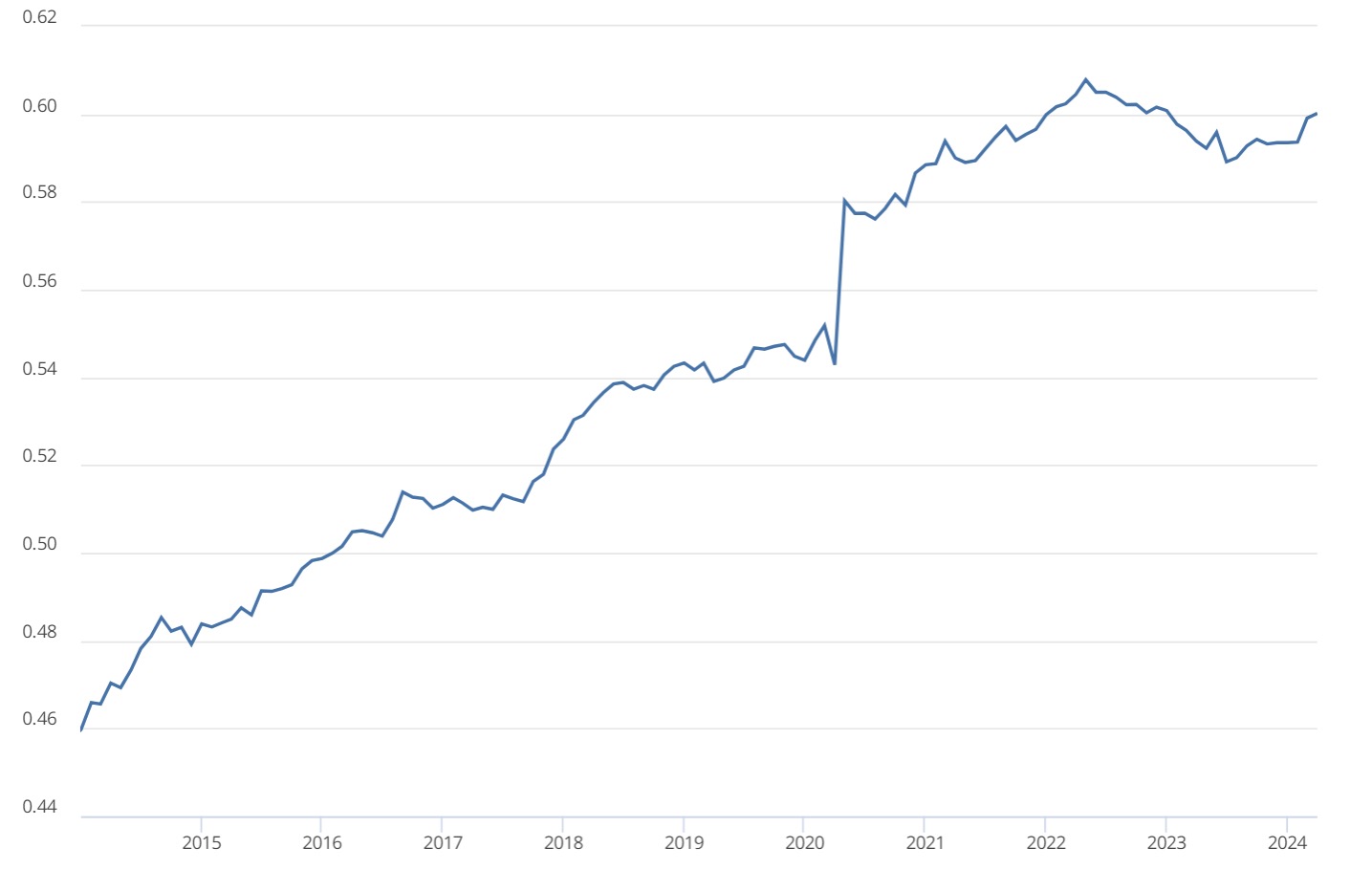

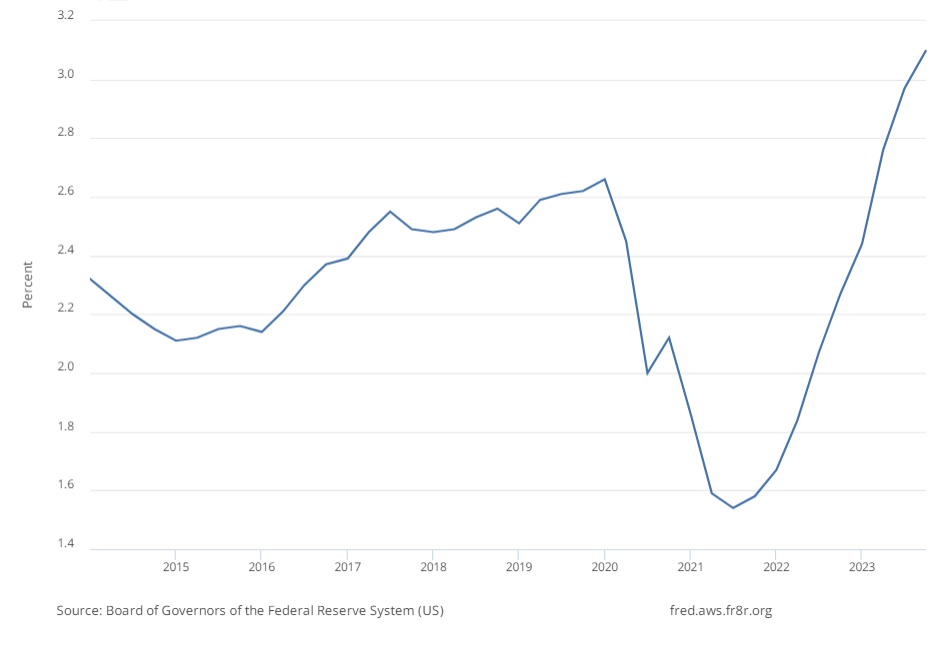

As discussed in previous communications I think the increases in transitions to delinquency of credit card debt and auto loans could be particularly problematic and may cause the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates.

Looking at long term interest rates, it is hard to know when markets will respond to the looming U.S. deficits. If AI generates sufficiently large increases in productivity, the primary deficit (the deficit leaving aside interest on the debt) as a fraction of GDP will not increase. While the overall deficit is likely to grow as a fraction of GDP because of increases in debt and increases in long term interest rates, the interest on government debt may be reinvested and thus enable the government to run deficits without unduly increasing pressures on inflation.

Regarding the long run effects of deficits generating ever-increasing levels of U.S. government debt, the critical unknown variables are the levels of total U.S. government debt as a fraction of U.S. and global GDP, and geo-political conditions that would cause foreign central banks and other institutions to reduce their holdings of U.S. debt. Massive selling of U.S government debt could cause a debt spiral. Price falls in the value of U.S. debt from this selling might trigger further reductions in holdings of U.S. debt. It is hard to know when this might happen. Currently some foreign central banks may be buying U.S. debt as a means of keeping their currencies from increasing in value against the dollar. I don’t think there is an imminent risk of foreign central banks dumping their holdings of U.S. debt because of fears of long term fiscal profligacy.1

Note that desired levels of private saving can offset the effects of large deficits. Japan has very low interest rates on its long term debt, despite private holdings of Japanese government debt of around 150% of GDP; total debt – including holdings by Japanese government controlled entities – is around 250% of GDP.

Risk of Recession

I believe that the low default rates are not a sign of corporations suddenly becoming safer, but rather a consequence of corporations having issued bonds at low interest rates in the past, and having fixed interest medium term loans. A large fraction of sub investment grade debt is coming due in the next 3 years. The low default rates on loans seem to be driven in part by a willingness of lenders to modify the loan terms. A large fraction of debt that was coming due in 2023 has been extended to 2024. If these “modifications” had occurred for bonds they would have been classified as default events.

The New York Fed survey is showing substantial increases in the flows into delinquency on credit card debt: the flow into serious delinquency (90+ days) increased from 4.01% in Q4 2022 to 6.86% in Q1 2024.

Delinquency Rate on Credit Card Loans, All Commercial Banks (2014-2023)2

Delinquency Rate on Consumer Loans, All Commercial Banks (2014-2023)3

Delinquency rates on loans to businesses are at historical lows, but that may be due to the $793 billion of loans/grants to small businesses from Trump’s Payroll Protection Program: over $750 billion of those loans have been forgiven.4 These large transfers to small and medium sized firms greatly increased their cash buffers and enabled them to cover losses. Until recently the nominal interest rate and the growth in wages (net of productivity improvements) has been below the Producer Price Index inflation rate. The PPI measures the prices of goods and services sold by domestic firms and thus along with changes in wages is a key macro-economic variable in determining the ability of firms to pay the interest on their loans.

Looking at the balance sheet side of the equation, the fall in the value of commercial property has probably not been fully recognized in balance sheets of both owners of real estate and of the banks that have commercial real estate as collateral on their loans. As I’ve mentioned previously, low defaults by businesses may be a sign not of fiscal prudence but rather of a combination of factors that have kept zombie firms afloat.

There are also problems of aggregation across the banking sector. Because stress tests are more onerous for larger banks, the large money center banks are well funded – this is less true of the smaller banks which have less onerous regulatory restrictions on the tier one capital. Note that the smaller community banks have a larger fraction of their assets in loans on commercial property compared with the large money center banks.

Risk of Trade War

Donald Trump is polling very high in the swing states despite a very strong economy (high interest rates hurt consumers, particularly ones with high credit card balances, which may explain the consumer sentiment readings that give Trump credit for better economic performance than Biden). The most obvious economic risk from a Trump election would be a trade war.5 He has said he will impose a 10% across the board increase in tariffs on all imports plus a 60% increase in tariffs on imports from China. The serious adverse effects arise if countries counter with taxes on U.S. exports, as China, Canada, India, and the EU did in the previous rounds of tariffs. China in particular imposed $34 billion of tariffs on imports from the U.S. The U.S. spent $23 billion on compensation for farmers that were hurt by retaliatory tariffs. In his first term, Trump did not counter the retaliation with further increases in tariffs so a trade war was averted, but Trump is now saying that he will respond to any retaliatory tariffs with matching increases in U.S. tariffs on top of the tariffs he is proposing. The resulting trade war could have devastating effects on U.S. exporters and U.S. producers that rely on imports in their production. There is also the risk that foreign governments could retaliate against U.S. firms generating profits from their overseas operations.

An escalating trade war could trigger a severe global recession. In the past the Republican Party has been a primary advocate of free trade (they provided the votes for NAFTA). Recent polling though has found that support for increased tariffs on foreign imports was highest among Republicans. There seems to be little resistance in either party to increases in tariffs, and little concern about the risk of a trade war.

Imports are around 15% of GDP. In the absence of retaliation, the expectation would be for a roughly 1.6% increase in prices and around a 0.5% decrease in GDP. The revenue from higher tariffs would help reduce deficits – it is effectively a consumption tax – so the total cost would be bearable. But a trade war and capital controls are a different story.

Explaining Inflation, GDP Growth, and Interest

Inflation is driven mainly by demand exceeding supply. The federal budget deficit and primary budget deficit in 2023 were 6.2% and 3.8% of GDP, respectively. They had averaged 3.8% and 2.0% respectively over the period 1994-2023. The primary deficit is perhaps more relevant than the total deficit. A large fraction of the national debt is held by the Fed and government agencies such as the Social Security Trust Fund and the Military retirement account. In those cases, the payments of interest are internal transfers and do not affect aggregate demand. Of the remainder, major holders include foreign central banks, pension funds, and insurance companies; their spending on U.S. goods and services is unlikely to be very responsive to changes in interest rates. Only a small fraction of the interest on U.S. debt is paid to U.S. individuals, and even in those cases these are likely to be high net worth individuals whose consumption is likely to be relatively inelastic with respect to changes to payouts of interest by the federal government.

While the aggregate accumulation of debt could affect the long run ability of the government to issue new debt, it is the components of the primary deficits that affect spending and thus inflation. The reason the 2017 tax cuts had relatively minor effects on inflation and employment was because the bulk of the benefits went to high net income individuals and corporations. High income individuals tend to have low marginal propensities to consume. The corporate sector spent a small fraction of its increased earnings from the tax cuts: it was mostly used for share buybacks and dividends or retained to improve balance sheets. The recipients of the increased dividends tend to be shareholders, who have low marginal propensities to consume. The buybacks and retained earnings also increased stock market valuations, but higher stock prices tend to have relatively small effects on consumer demand in the short to medium term.

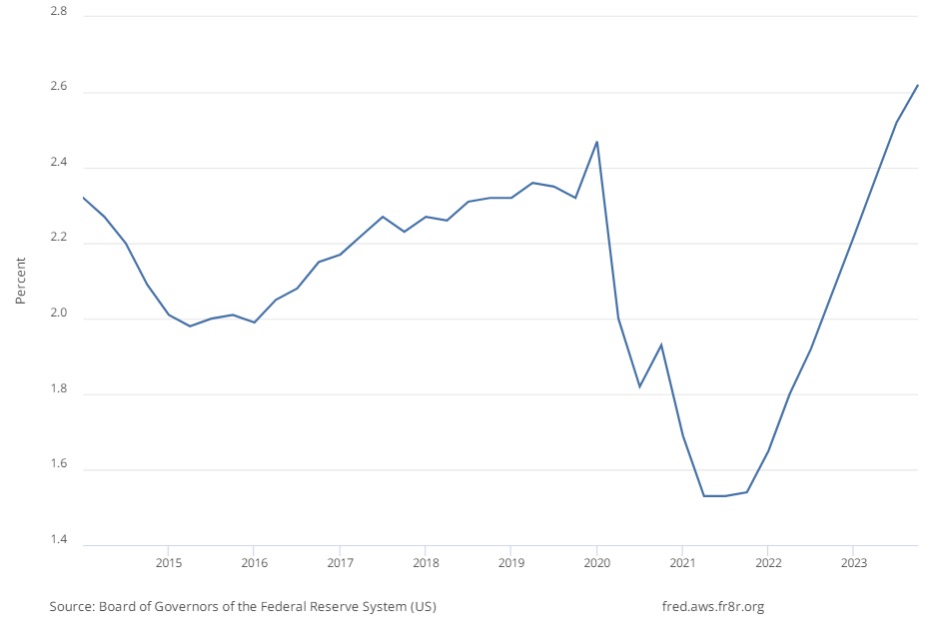

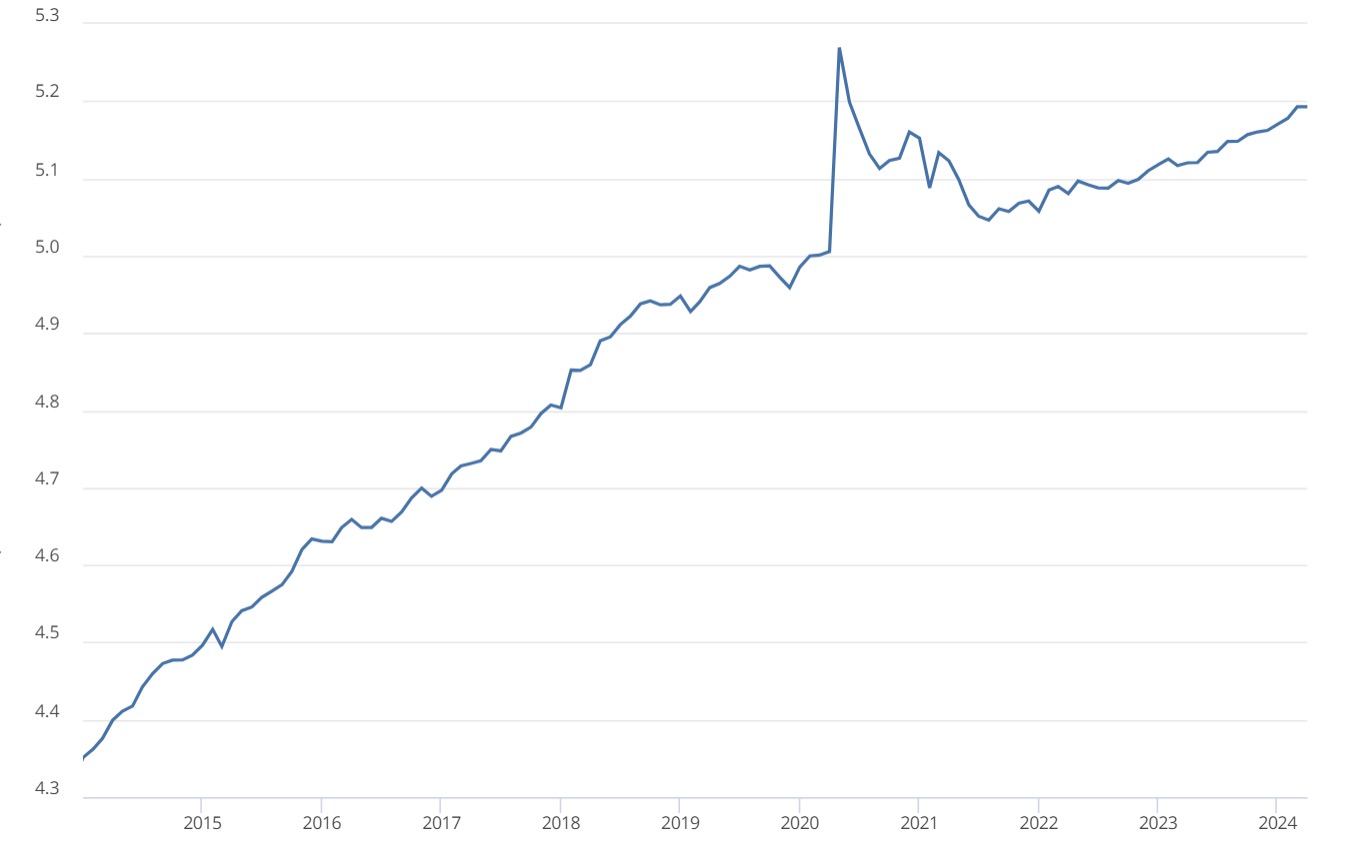

Looking forward, increases in direct payments to poor families with children and reductions in the interest payments on student debt for lower income individuals are likely to have a much larger immediate effect on spending and thus on inflation than are tax cuts to entities with higher savings rates. The infrastructure bill, CHIPS Act, and the subsidies and tax breaks in the “Inflation Reduction Act” that encourage spending on plant and equipment may increase supply in the long run but in the short run will be pushing up prices. As can be seen in the figures below, starting in October 2022, employment in non-residential construction has been growing rapidly as a fraction of all full-time employment.

The delays in the planning, financing, approval, and permitting of projects that were incentivized from these various programs mean that the stimulus from the non-residential construction seems likely to continue and may outweigh the dampening effects from the depletion of excess savings that accrued from the direct stimulus payments. The increase in employment in non-residential building construction does not appear to have had a serious negative impact on employment in residential construction, which has been roughly constant during the recent run up in mortgage interest rates; however, permits for residential construction fell sharply in 2022 such that due to delays between permits and housing starts we may expect to see falls in employment in residential building in the near future.

Why hasn’t restrictive monetary policy offset this expansionary fiscal policy and blocked inflation? The standard answer is that there are long delays in the impact of interest rate changes. But the delays seem longer than expected from historic experience. The argument I’m going to make is that the macro-economic models overestimate the effectiveness of monetary policy in the current environment.

Monetary policy mainly involves the choice of the short term interest rate on bank deposits at the Fed and on reverse repo transactions. By increasing those interest rates, the Fed drains money out of the banking system, increasing the interest rates charged on loans (it also increases the interest paid on savings, more on that anon). The higher interest rate on loans mainly affects the motor vehicle and construction industries. But manufacturing of motor vehicles and parts is a small fraction of total employment. Employment in manufacturing of motor vehicles and parts in March was approximately 0.7% of total employment, and despite the large increase in interest rates, employment in this sector as a fraction of total employment has been fairly constant – even rising slightly – over the last 3 years. The continued demand for motor vehicles in the face of high interest rates may be a residual effect of the increase in savings from the stimulus packages and supply constraints during the pandemic. People who bought used motor vehicles during that period because the models of the new motor vehicles weren’t available may be exchanging those older used cars for new cars (the number of used cars sold is roughly double the number of new ones sold).

Turning to construction, employment in construction as a fraction of total nonfarm employment is higher than pre-pandemic levels. A flattening in employment in residential construction as a fraction of total employment has been more than offset by an increase in employment in non-residential construction. Any negative effects of higher interest rates appear to have been more than offset by the construction spending due to the various stimulus packages. Because of delays in approvals and permitting, the infrastructure bill and the CHIPS Act have not yet had their maximum impact. Eventually the fall in the value of commercial real estate may cause spending on non-residential construction to fall.

For the near term the high levels of employment in non-residential construction seem likely to continue.

All Employees, Construction6 / All Employees, Total Nonfarm7 (Percentage, 2014-2024)

All Employees, Residential Building Construction8 / All Employees, Total Nonfarm9 (Percentage, 2014-2024)

All Employees, Nonresidential Building Construction10 / All Employees, Total Nonfarm11 (Percentage, 2014-2024)

Roughly 31% of purchases are made with credit cards, and around half of credit card holders have balances on which they are being charged interest. Interest rates on credit card balances have increased from around 16% to around 21%, which would have a significant effect on the cost of goods for consumers with outstanding balances.12

The other way interest rates affect demand is through the savings rate. When the Federal Reserve increases interest rates, this affects the interest rates paid on savings. The effects are immediate for people invested in money market funds and who own savings bonds or other variable rate savings instruments. The effects of higher interest rates are cumulative as people move money out of zero interest or low interest accounts at banks and into higher interest rate money market accounts.

The higher interest rates on savings are usually assumed to increase savings, but this assumption is not a consequence of economic theory. Higher real after-tax interest rates on savings enable the consumer to buy more goods and services in the future if they forgo consumption today. On the other hand, higher interest rates on savings make the consumer richer in the future and consumption smoothing (decreasing marginal utility of consumption) would dictate spending more now in response to the higher interest rates. Economic theory doesn’t say which effect should dominate. The historical data is not capable of resolving which effect dominates. Until the early 1980s, the interest rates banks could charge on deposits were severely regulated, and participation in money market funds is a fairly recent phenomenon so the interest rates paid on savings did not vary very much. The recent data has not yet been analyzed and, since so much of savings is done by high net worth individuals, an analysis of these effects would require analyzing the after-tax return on savings compared with the anticipated changes in the prices of goods that high income individuals purchase and for which they can time their purchases. My best guess would be that the effects of higher nominal interest rates on savings are small. There may be a larger effect on the allocation of savings between equities and money market accounts or between short term debt instruments and long term debt instruments. These reallocation effects could have large long run implications for the economy, but seem unlikely to have major short run effects on the prices of the goods and services used to measure the consumer price index.

Longer Term Financial Conditions

Republicans are supportive of tax cuts funded by unspecified cuts in domestic spending other than entitlement programs or spending on national defense. The more radical elements of the Republican Party are not even supportive of offsetting tax cuts with tax reforms that recapture the losses from the excess payouts in the Payroll Protection Program. Democrats are seeking increased spending on domestic programs like the child care credit, student debt forgiveness, and subsidies for investments in green energy and domestic manufacturing that would be funded by increased taxes on the wealthy – that are highly unlikely to pass Congress. Neither side seems be prioritizing measures that would address long term fiscal imbalances.

The revenue enhancing measures that have bipartisan support would appear to be tariffs. Since imports are only around 15% of GDP, and since tariffs will reduce the size of imports, the levels of tariffs high enough to make a meaningful dent in the long run budget deficits would likely trigger a trade war that could result in a global recession. I fear that the “compromise” will be unfunded increases in spending and possibly additional tax cuts that would accelerate the dates at which the fiscal imbalances in the U.S. budget become unsustainable.

Projections of Future Deficits

When it makes projections of future budget deficits, the Congressional Budget Office (“CBO”) is required to assume that the tax cuts that are scheduled to expire in 2025 will not be extended. This results in the CBO assuming that tax receipts will increase substantially after 2025. The CBO is also required to assume that defense spending will grow with inflation rather than with GDP (that would eventually result in defense spending falling below the 2% of GDP that we are advocating as a minimum for all NATO members). Both of these assumptions seem implausible. For instance I would be astonished if Congress allows the standard deductions to go back to their previous levels – greatly increasing the taxes for many people and increasing the hassle and costs of filing their returns. Turning to the defense budget, given the military spending of Russia, China, and North Korea, I’d be very surprised if the defense spending were to begin to fall as a fraction of GDP in the imminent future.

I do not have an opinion about what is the right level of defense spending, and while I have opinions about spending on child care, industrial policy, and forgiveness of student debt, I have no particular expertise in those subjects and will not bloviate about them. I have the more modest goal of pointing out that the reluctance of government to address the looming deficits is imposing serious long run risks to the U.S. economy.

The solutions I favor are:

- An alternate minimum tax on consumption. This would be a progressive consumption tax that would collect taxes from people with high levels of consumption who are not paying correspondingly large taxes. I have written more on this subject previously. Read here.

- Reforms to Social Security that would incentivize people to delay retirement. This would increase labor supply and tax revenue and reduce spending on Medicare since some of the retirees would benefit from company provided medical insurance.

- Making greater use of taxes on pollutants and email spam to guide behavior rather than regulations and subsidies.

Sincerely,

Andrew Weiss | CEO, Weiss Asset Management

Disclaimers:

This commentary has been prepared by Dr. Andrew Weiss and reflects the opinions of Dr. Weiss. This is not an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to buy any security of any fund (a “Fund”) managed by Weiss Asset Management LP or its affiliates (“WAM”) or any other investment product or strategy. Offers to sell or solicitations to invest in a Fund are made only by means of a confidential offering memorandum and in accordance with applicable securities laws. An investment in a Fund involves a high degree of risk and is suitable only for sophisticated investors that are qualified to invest therein. Commodity trading involves a substantial risk of loss.

This commentary may not be reproduced or further distributed without the written permission of Dr. Weiss. This material has been prepared from original sources and data believed to be reliable. However, no representations are made as to the accuracy or completeness thereof.

Although not generally stated throughout, this commentary reflects the opinion of Dr. Weiss, which opinion is subject to change and neither Dr. Weiss nor WAM shall have any obligation to inform you of any such changes.

This commentary includes forward-looking statements, including projections of future economic conditions. Neither Dr. Weiss nor WAM makes any representation, warranty, guaranty or other assurance whatsoever that any of such forward-looking statements will prove to be accurate. There is a substantial likelihood that at least some, if not all, of the forward-looking statements included in this commentary will prove to be inaccurate, possibly to a significant degree.